Imagem

Reflexão

Casa Grande & Senzala

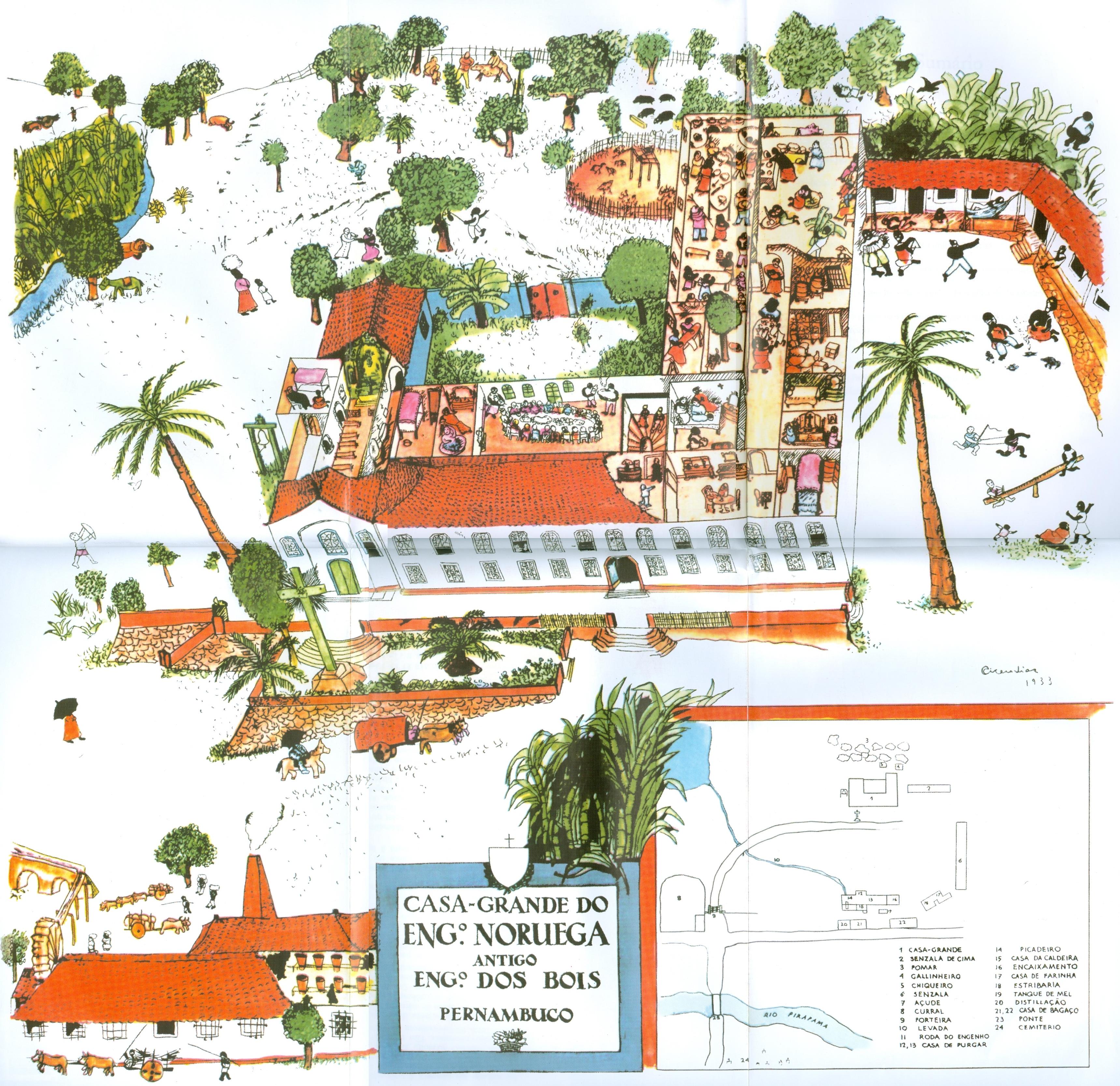

Illustration from the book ‘Casa Grande e Senzala’ by Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre, published in 1933.

The Casa Grande and Senzala, represented here in the picture, referred to the land and dwellings of the so-called ‘plantation lords’, i.e. the slaveholders who owned a sugar mill on their land and the senzala, the place where the enslaved were kept and imprisoned.

The Casa Grande &Senzala, more than a physical space, is a specific microcosm through which it is possible to understand the social, political, economic and racial dynamics of the time. Freyre uses the concept of Casa Grande to emphasise its importance in the formation of Brazilian society, arguing in its favour and in favour of the - forced - miscegenation between whites (slaveholders) and blacks (enslaved).

In the picture you can understand the size and complexity of this space, where the plantation owner and his white family lived, but also enslaved blacks who worked in the fields, in the sugar mill and, some, in the Casa Grande.

Although Gilberto Freyre speaks of this structure as something positive, his argument does incorporate racist and colonial ideas, as can be understood by the caricatured representation of black people in the image, for example. His book gained notable importance on the topic, not least because it spawned the concept of ‘luso-tropicalism’, which argues that the Portuguese colonisers were exceptionally open to miscegenation and cultural ‘mixing’, thus justifying the entire hierarchical and slave-like social structure of the time.

This concept was initially rejected in Portugal, since this contact between slave and enslaved only happened in the colonised territories and not in Portugal, and therefore social relations between the two groups were not the same as in Brazil. It was only later, during Salazar's dictatorship, that the concept was strategically used to relativise the violence of the colonial war that was taking place in African territories. Ideas such as ‘brotherhood between races’ were widely used to hide the truth about the war and, above all, to hide the racist motivations behind the colonial violence.

The idea that ‘Portugal is not a racist country’, used more recently by far-right groups in Portugal, is directly linked to the rejection of racism and violence in the colonial process that Luso-tropicalism provided.